Watch movements, which are also called calibers, are an integral part of any timepiece. Like an engine in a car, a movement is what powers a watch and regulates its functions. While the vast majority of people will buy a luxury watch based on design and price, true enthusiasts also consider the type of movement that’s inside the case. If you’re unsure about watch calibers or are just looking to learn more, here’s a primer on watch movements so you can learn the basics.

Movement Types

The movement a watchmaker uses determines the type of features a watch will have, how the watch gets its power, and what type of maintenance it will need. Furthermore, a watch movement also plays a part in the cost and collectibility of the watch, as some are more complicated to build than others.

There are two main types of watch movements: mechanical movements and quartz movements.

Manual movements and automatic movements are both mechanical movements. They’re comprised of mechanical components such as gears, trains, and wheels.

On the other hand, quartz movements have electrical circuit boards and batteries.

Mechanical movements are typically more expensive and desirable while quartz movements are more practical, affordable, and accurate.

One quick way to tell whether a watch runs on a mechanical or quartz movement is to look at the seconds hand on the dial. Generally speaking, If the hand “jumps” to the next position once every second (accompanied by a loud “tick), it is a quartz watch. Conversely, if the hand “sweeps” around the dial, requiring five to ten pulses (depending on the frequency of the movement) to reach the next seconds position (accompanied by softer but more frequent ticking), then it’s a mechanical watch.

Mechanical Movements: Manual and Automatic

Mechanical movements are powered by a coiled spring (called the mainspring) that drives a set of tiny mechanical parts. Watches with these movements can be broken down into two main sub-categories:

- Manual: the mainspring must be manually wound using the crown

- Automatic: the mainspring is wound by a metal weight that rotates free and recharges with its wearer’s movement

Mechanical movements are generally comprised of the following parts:

- Winding crown on the exterior of the case, which serves to wind up the mainspring

- Mainspring, which stores the energy

- Gear train, which is a group of gears that serve to transmit the energy from the mainspring to the escapement

- Escapement, which regulates and distributes the energy in equal parts to the balance wheel

- Balance wheel, which takes the lateral pulses from the escapement and oscillates at a constant frequency to regulate the movement. Mechanical movement balance wheels can oscillate anywhere from 18,000 to 36,000 beats per hour.

- Dial train, which takes the constant beats of the balance wheel to move the hands on the dial forward

One feature that is often discussed when talking about watch movements is power reserve, also known as réserve de marche in French. A movement’s power reserve tells you how long it will run when it is fully wound.

Manual Movements

Manual movements (also known as hand-wound movements or manual-winding movements) are the most traditional and oldest type of mechanical movements. Most require daily winding to keep the watch running. However, there are some hand-wound watches that boast 8, 10, or even 14-day power reserves. A. Lange & Söhne introduced the Lange 31 in 2017, which is the world’s first mechanical wristwatch (wound via a key) with a power reserve of 31 days. The Vacheron Constantin Traditionnelle Twin Beat Perpetual Calendar has a clever movement that can be slowed down when it’s not worn to guarantee an extended power reserve of at least 65 days.

One of the main benefits of manual movements is that they’re slim in profile. Therefore, they’re often used in elegant ultra-thin dress watches.

Don’t Miss: The Rebirth of the Men’s Dress Watch

Automatic Movements

Automatic movements (also known as self-winding movements) are also mechanical movements but they have the addition of a rotor. A rotor is a semi-circular metal weight that swings freely with a wrist’s natural motion, which in turn winds the mainspring. So, as long as you wear an automatic watch (or store it in a winder), it will continue to run.

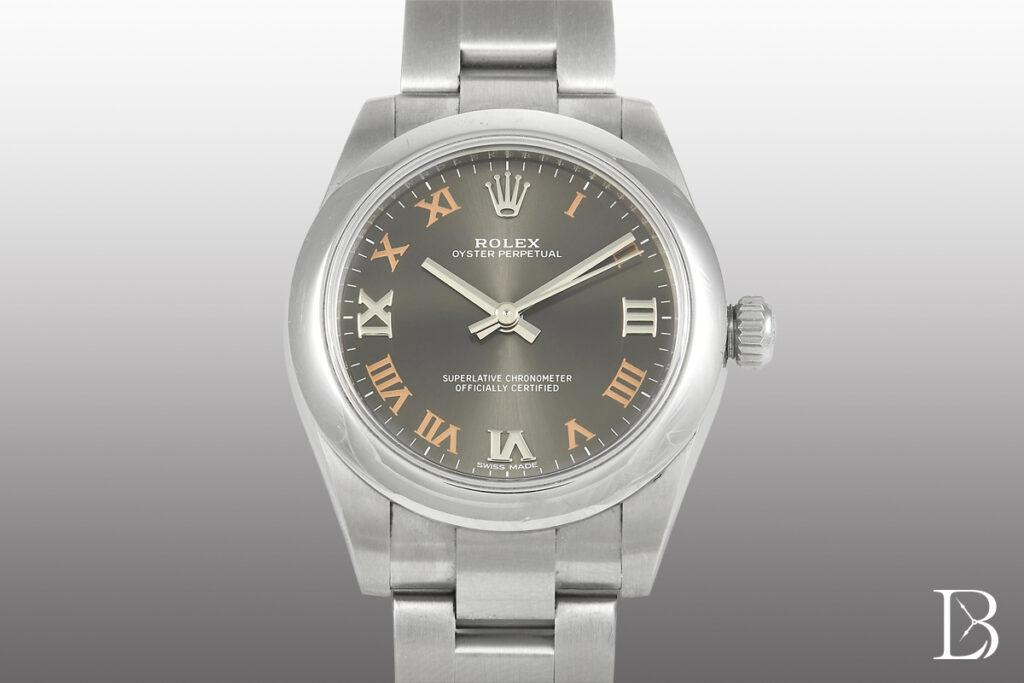

Self-winding watches are normally thicker than manual-winding watches to accommodate the rotor. Rolex popularized self-winding wristwatches when it introduced its “Perpetual” movement with a rotor in 1931.

Price Guide: What is the Price of a Rolex Oyster Perpetual Datejust?

Most luxury automatic watches will have a power reserve anywhere between 36 and 72 hours, although some can last seven or more days. For instance, IWC makes automatic movements with 7-day power reserves and Panerai has automatic movements that will continue to work for 10 days on a full wind.

Automatic watches can also be manually wound using the winding crown if needed.

Quartz Movements

Quartz movements are newer than mechanical movements and generally don’t require the same type of upkeep. These watches will continue to run as long as the watch battery has power—there are no winding requirements with a quartz watch.

Quartz movements are generally comprised of the following parts:

- Battery, which is the power source of the watch

- Integrated circuit, which transmits energy from the battery to the quartz crystal and transmits electrical pulses from the quartz crystal to the stepping motor

- Quartz crystal, which oscillates at a precise frequency of 32,768 times each second

- Stepping motor, which releases every 32,768th electrical pulse to the dial train

- Dial train, which takes the constant pulses of the stepping motor (1 per second) to move the hands on the dial forward

Discover: Rolex Quartz Watches: The Complete Guide

While most quartz watches use disposable batteries (which have to be replaced every two to five years) there some quartz watches rely on rechargeable batteries too. For instance, there are solar-powered batteries that charge with light and kinetic-powered batteries that charge with the wrist’s motion. Plus, there are watches that you plug in that charge with electricity.

Solar-Powered Watches

This is the most recent solution that companies like Citizen have taken up a few years ago with the production of their Eco-Drive and similar models. The first models of solar-powered watches had a great defect of being easily damaged, especially if left unused for a long time.

Today, this type of watch movement offers considerable precision; some of Citizen’s Eco-Drives, in particular, are radio-controlled, that is, they receive the time reading from atomic clocks, absolutely precise timepieces that are based on their resonance frequency of an atom, and are operated in several laboratories around the world.

Spring Drive Movement

Many Grand Seiko watches are powered by a Spring Drive movement type, which is a hybrid between quartz and mechanical. A Spring Drive is powered by a mainspring (like a mechanical movement) but it incorporates a quartz crystal oscillator to deliver an accuracy rating of +/- 15 seconds a month, equivalent to one second a day.

Historical Perspective: The Quartz Crisis

Seiko debuted the Astron as the world’s first quartz wristwatch in 1969, which was the start of the two-decade period that would later be known as the Quartz Crisis. Given that quartz movements are more accurate and cheaper to produce than mechanical movements, quartz watches largely replaced traditional mechanical timepieces throughout the 1970s and 1980s, which just about decimated the Swiss watch industry.

It’s important to note that while Switzerland and Europe refer to this era as the Quartz Crisis, Japan and Asia call it the Quartz Revolution. It’s a matter of perspective.

Towards the end of the 1980s and the onset of the 1990s, mechanical movements began their comeback as the more prestigious option—particularly Swiss-made ones. While most of the world’s watches run on quartz movements today, mechanical movements are generally preferred for high-end timepieces since they require more skill, knowledge, and craftsmanship to manufacture.

Electric Watches

Before the onset of quartz timepieces, there were electric watches, pioneered by companies such as Elgin, Hamilton, Timex, Bulova, and others. One of the most famous – and appreciated by watch enthusiasts – is the Bulova Accutron. It was special because it replaced the balance wheel (the timekeeping element of mechanical watches) with a tuning fork, which vibrated with a frequency that was much higher than the traditional balance wheel.

With this kind of system, the precision and fluidity of the movement increase considerably, and the second-hand moved very smoothly. Electric watches eventually gave way to quartz watches as the latter were more commercially viable and robust.

What is a Chronometer? Who is COSC?

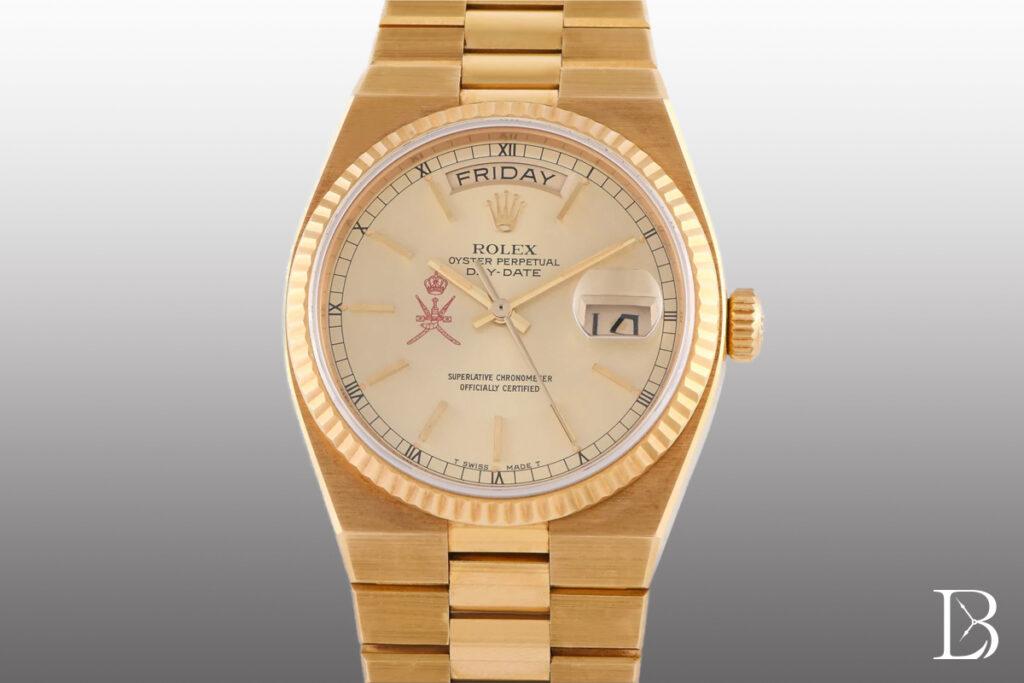

A chronometer is the name given to high-precision timepieces, which are certified as such only after passing a series of rigorous tests. In Switzerland, the Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres (COSC)—or Official Swiss Chronometer Testing Institute in English—is responsible for certifying Swiss watches as chronometers.

Mechanical and quartz watches can be chronometers and COSC certifies around 1.8 million watches a year, complete with a unique ID number engraved on the movement and a certificate.

Mechanical watches are subjected to 15 days of testing across different temperatures and positions. Among other criteria, a mechanical watch must maintain an average daily rate of -4/+6 seconds a day to be certified as a chronometer.

Although quartz movements are more precise than mechanical movements by nature, they are more susceptible to temperature and humidity, which can affect their precision. Therefore a quartz chronometer undergoes 13 days of testing at three different temperatures and four different humidity levels.

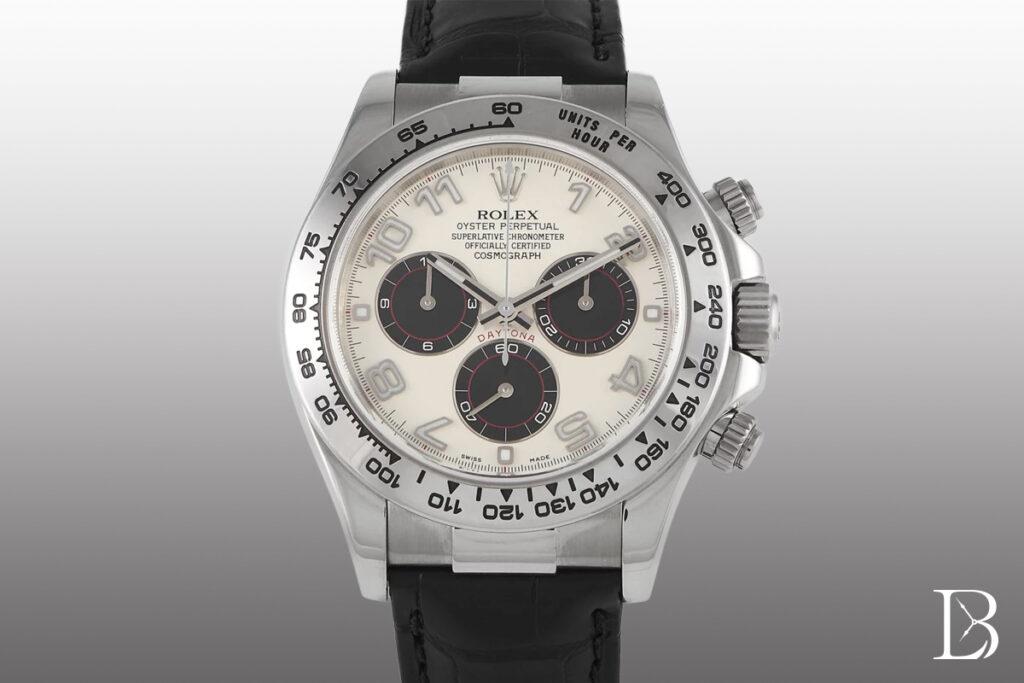

While the words chronometer and chronograph are often mixed up, they are not the same thing. As explained, a chronometer is a very accurate timepiece. On the other hand, a chronograph is a watch with a stopwatch function.

Watch Complications

Aside from power, a watch movement will determine the type of functions a timepiece will have. Any function that goes beyond telling the time is called a “complication” in watch-speak. Some examples include calendar indications, multiple time zones, chiming mechanisms, and stopwatch capabilities. The more complications a watch has, the more intricate (and expensive) its movement has to be.

Learn about watch complications:

What is a GMT Watch?

What is a Chronograph Watch?

What is an Annual Calendar Watch?

What is a Perpetual Calendar Watch?

What is a World Time Watch?

What is a Minute Repeater Watch?

What is a Tourbillon Watch?

What is a Grand Complication Watch?

Watch on Grey Market TV: The CRAZIEST Watch Complications EVER! Unveiled…

In-House vs. Modified Movements

Watch brands can choose whether to develop and build their watch movements in-house from the ground up or take a base movement (called an ébauche) and modify it according to what is needed for the watch. For most of its history, the Swiss watch industry was comprised of a network of artisans and craftspeople that were specialized in making different components of watches. For instance, there were dial makers, case makers, bracelet makers, and of course, movement makers.

Very few brands historically made all (if any) watch movements in-house. Instead, most brands would source components from various specialists and assemble the watches according to their design and mechanical specifications and then sell the completed wristwatches under their name. Some famed past movement makers include Peseux, Lemania, and Valjoux, which were all eventually consolidated and absorbed by ETA SA Manufacture Horlogère Suisse—the largest manufacturer of Swiss ébauches and movements today.

However, over recent decades, more and more luxury watch companies are manufacturing as many movements in-house as possible. In turn, more luxury watch consumers are expecting high-end watches to run on in-house calibers. In-house-made movements are often called manufacture movements.

While no hard and fast rule says an in-house movement is necessarily better than a modified ébauche, a manufacture movement is typically perceived as more prestigious.

Movement Finishing and Decoration

The finest watch brands not only ensure that the timepiece exterior is beautiful but they also take painstaking care that movements are impeccably finished and decorated. Some watches even have exhibition casebacks (where the back of the watch is furnished with transparent glass) so a decorated movement can be admired.

In addition to being aesthetically pleasing, movement finishing historically also served a functional role by making certain parts more corrosion-resistant or keeping dust away from the most sensitive components. Furthermore, steel turns into a rich blue color after being exposed to high heat, which explains the ubiquity of “blued steel” watch parts.

Common Movement Finishing Techniques

Some of the most traditional finishing and decorative techniques, whether done by hand or machine, include:

- Anglage: French for beveling/chamfering

- Black Polish: results in a perfectly smooth surface of steel parts, which can reflect like a mirror or look black depending on the angle

- Geneva Stripes: parallel wave-like patterns, which can be circular or straight

- Perlage (a.k.a. circular-graining or stippling): overlapping circular pattern

- Engraving: various parts of the movement can be engraved with brand names, numbers, text, or decorative patterns

The Poinçon de Genève, or the Geneva Seal, is a certificate awarded to timepieces that have movements that are decorated and finished to a certain standard. The criterion is strict and includes several movement components such as baseplates, bridges, balance wheels, balance springs, wheel trains, screws, and pins. As its name implies, the Poinçon de Genève can only be awarded to Geneva-based watchmakers

Choosing the Right Type of Movement

The movement type is important to consider when buying a watch. If you want something super-low maintenance, cheaper, and accurate, then a quartz movement may be for you. However, these are considered less prestigious, so bear that in mind.

On the other hand, if you want something ultra-traditional then a manual-winding mechanical movement may be more your pace. Many owners of manual watches find the hands-on approach appealing and feel even more connected to their timepieces because they have to wind it on a regular basis.

If you appreciate mechanical movements but don’t necessarily want to wind a watch daily (or every few days), then an automatic is a great choice. It’ll keep on going as long as you wear it and you can even store it in a watch winder when you’re not wearing it.

So, the next time you’re thinking of buying a new watch, pay attention to the type of movement that’s housed inside the case so you can decide on the best option for your needs.