Rolex Trademarks “Tru-Beat” Again: Why?

When the original Rolex Tru-Beat debuted in 1954, quartz watches didn’t exist yet. And usually, mechanical watches appear to “sweep” as they beat several times per second. So the once-per-second tick of the Tru-Beat was novel in its day, and useful for doctors measuring pulses–though its production only lasted about eight years. But Rolex filed for the “Tru-Beat” trademark in spring of 2025, and it could mean they’re reviving the model–or it could mean nothing at all.

What the Tru-Beat Trademark Means

The filing of the Rolex Tru-Beat trademark doesn’t necessarily mean much because Rolex’s history is littered with unused patents and trademarks. They could simply be covering their bases and deterring competitors from using them.

For context, from 2023-2025, Rolex trademarked a slew of names including Danaos, Cellissima, Oysterquartz, Master Day-Date, Master-Datejust, Zetex, Coast-Dweller and Space-Dweller, some of which are old familiar model names and some of which are brand new (like “Coast-Dweller”). Interestingly, they also filed for a trademark for the phrase “For it is all we do. But we do it all,” presumably implying that they only make watches–although a Rolex accessories section appeared on their website recently.

Under U.S. law, trademarks can be subject to cancellation after three consecutive years without bona fide commercial use, and under Swiss law that figure is five years. In short, trademarks are largely a “use it or lose it” situation so if Rolex does nothing with a trademark, a competitor could eventually file for its cancellation. I expect Rolex to ultimately let most of these trademarks fall into disuse, but even an abandoned trademark can be a procedural speedbump for a competitor wishing to use it.

History of Deadbeat Seconds

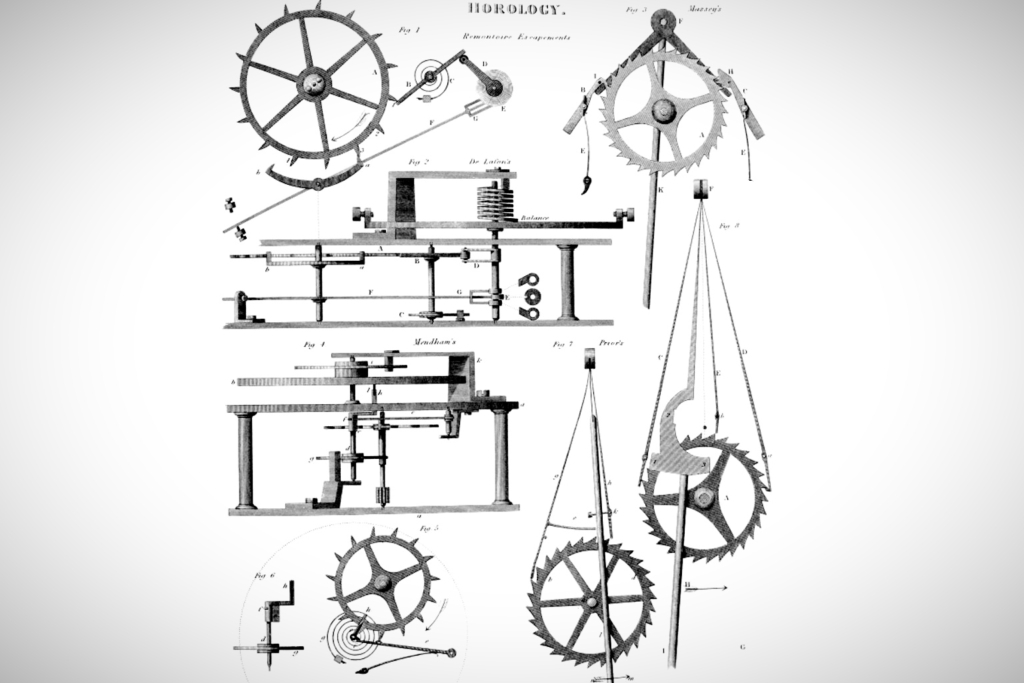

Although the Rolex Tru-Beat was one of the first wristwatches to tick once per second when it debuted in 1954, the concept was already a quarter-millenium old. The origin of the deadbeat seconds complication (also known as jumping seconds or seconde morte) dates back to 1675, when English scientist Richard Towneley created a deadbeat escapement for use in regulator clocks. It was refined and popularized by British clockmaker George Graham 40 years later, but the wristwatch era was still far off.

Bizarrely, three companies–Omega, Rolex, and Chézard (who was owned by Ebauches SA and supplied movements to Doxa, Zenith, Dugena and others)–all released deadbeat seconds watches in 1954. Ebauches SA was granted a patent for deadbeat seconds wristwatch movement in 1950 but it’s unclear who was actually first to market, and frankly I’ve never heard any explanation as to why such an obscure complication appeared from three companies almost simultaneously.

All of these watches use a star-and-flirt system, meaning a spring-loaded lever called a “flirt” is continually pressing against a star-shaped gear. With every beat of the watch, the star rotates, but only one tooth is the “release tooth,” which actually allows the flirt to release and thus advance the seconds hand.

So because the Rolex Tru-Beat movement beats 5 times per second, its star has 5 points–and thus its seconds hand advances once per second. My theory is that Ebauches SA’s patent for a star-and-flirt system might have actually enabled Omega and Rolex to make their own versions of it, although they’re different enough not to infringe on the patent.

And it’s worth noting that a star-and-flirt mechanism isn’t the only way to achieve deadbeat seconds. A remontoire is a complex, generally expensive mechanism designed to store and release small bursts of energy at regular intervals, thereby delivering consistent force to the escapement (and thus consistent timekeeping) whether the power reserve is full or nearly empty.

Some remontoires release their energy once per second, and in those cases watchmakers can directly drive a deadbeat seconds hand as a “natural byproduct” of the mechanism’s constant-force function. The F.P. Journe Tourbillon Souverain, Arnold & Son Constant Force Tourbillon, Greubel Forsey Différentiel d’Égalité, Lang & Heyne Friedrich II Remontoir, and Urban Jürgensen UJ1 Tourbillon are all examples of that concept. And uniquely, the A. Lange & Söhne Richard Lange Jumping Seconds uses both a remontoire and a star-and-flirt.

The Rolex Tru-Beat Trademark and the CPO Theory

Rolex launched their Certified Pre-Owned program in 2022 and they’ve steadily been expanding it to include more and more of their authorized dealers. Rolex has also been increasingly eliminating parts accounts–meaning independent (but still Rolex-certified) watchmakers that can order genuine Rolex parts for repairs. When you combine this landscape with legal actions like the Rolex v. Beckertime lawsuit, many people get the impression that Rolex is trying to exert a tighter control on the secondhand market of their watches in general.

So, if they plan on selling a lot of old Rolex Tru-Beat, Cellissima, Oysterquartz and Danaos watches through their CPO program, it makes sense that they would want to try to lock up those terms so their competitors can’t use anything similar for a while. But servicing and certifying watches is unlikely to satisfy the definition of commercial use when it comes to trademark retention.

Although Rolex has filed for an as-yet-unapproved patent for an “Energy storage system for a mechanical watch,” I don’t think it’s referring to the energy that gets stored and released each second in a deadbeat-seconds watch. Its international patent code, G04B1/14 (2006.01) specifically relates to the design, construction, materials, or arrangements of mainsprings and any attached bridle mechanisms. A deadbeat seconds escapement would have a different code (probably G04B13/002 or G04B15/10).

Vintage Rolex Tru-Beat Market

Today, a nice stainless steel vintage Rolex Tru-Beat is worth about $25,000 if the deadbeat seconds mechanism is working. But if it’s not working–which is the norm–the seconds hand will simply tick at a typical rate of five times per second and the value plummets to somewhere around $8,500. Gold models are rare and can easily be worth double.

With its 34mm case and 19mm lug width, the Tru-Beat ref. 6556 and 6558, aside from the seconde morte feature, is very similar to a common Rolex Air-King 5500. The ones with crosshair dials and red seconds hands are sweet, though, and if Rolex does bring the Tru-Beat back–and I’m certainly not saying they will–I hope those visual cues return too.

Leave a Reply