The Watch Industry the Quartz Crisis Really Destroyed: The American One

People often talk about how the “quartz crisis”–the time period in the 1970’s when then-new quartz watches began to supersede mechanical ones–nearly destroyed the Swiss watchmaking industry. Well, it didn’t. But it decimated American watch firms. A number of factors were at play, and the invention of quartz oscillators was arguably not even the main one. Here I’ll tell the story of the rise and fall of the American watch industry.

A Brief Summary of American Watchmaking Innovation

The industrialization of watch production actually originated in the United States in the 1850’s, and American railroad timekeeping standards of the 1890’s shaped the global watch industry’s approach to standardization. But Switzerland began to seriously overtake the American watch industry around WWI, and few American watch firms survived the Great Depression unscathed.

In 1960, the Bulova Accutron–the world’s first electronic wristwatch–made the US look like a re-emerging leader in the watch world. Yet within a few years of quartz watches hitting the market, nearly the whole American watchmaking industry was gone. Let’s start at the beginning of the industrial era.

Massachusetts: The Birthplace of Industrial Watchmaking

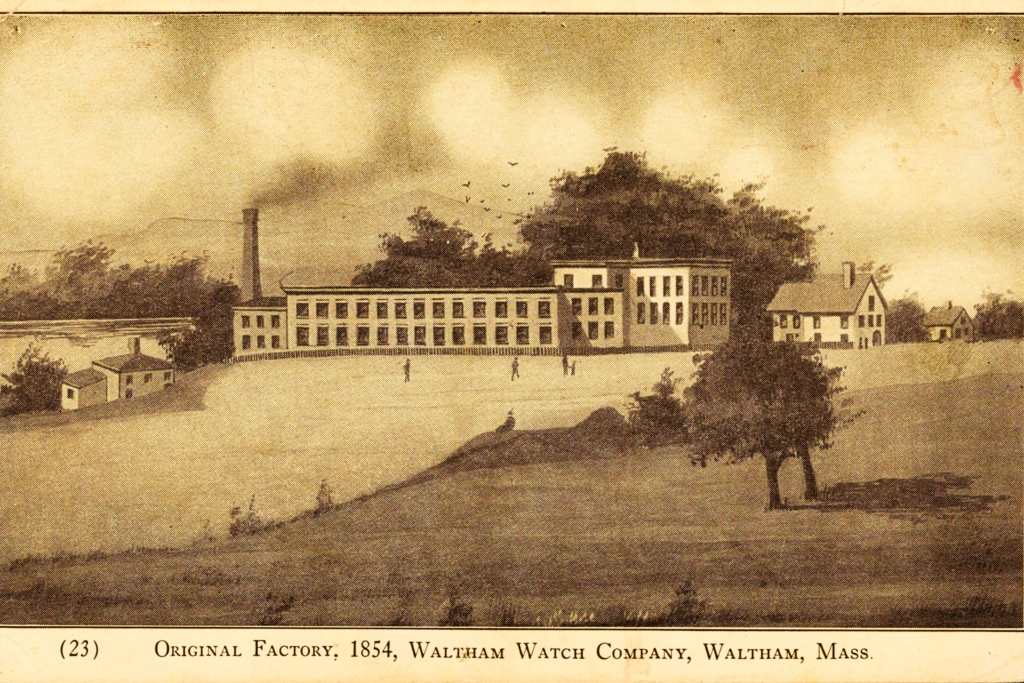

In 1807, the first-ever mass-produced clocks were made by Eli Terry using waterpower-operated machines in Connecticut. Aaron Lufkin Dennison hoped to bring that “American system” to pocket watches. The mass production of watches essentially began in 1854 when Lufkin’s company, Boston Watch Company (which would be renamed American Watch Company and then Waltham Watch Company), built a factory on the banks of the Charles River in Waltham, Massachusetts.

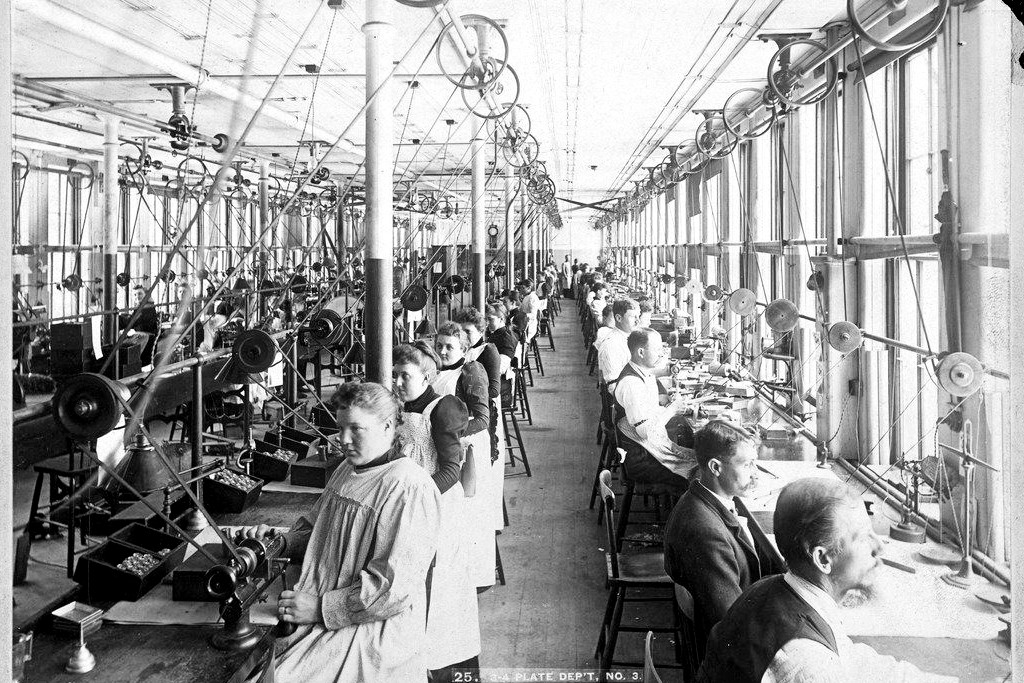

There, they could take advantage of the hydropower provided by the river’s natural drop. Waltham thus became the first company in the world to mass-produce complete watches under one roof using standardized, machine-made components. They are widely credited with introducing interchangeable parts to the watch industry.

I should note that While the Americans were the first to industrialize watchmaking, the Swiss were still years ahead in terms of high-end escapements and balance springs. That’s why Dennison briefly moved to Switzerland to oversee some parts manufacturing there, before ultimately starting a notable case making company in England. Waltham carried on under new ownership.

The American Watch Industry Scared the Swiss

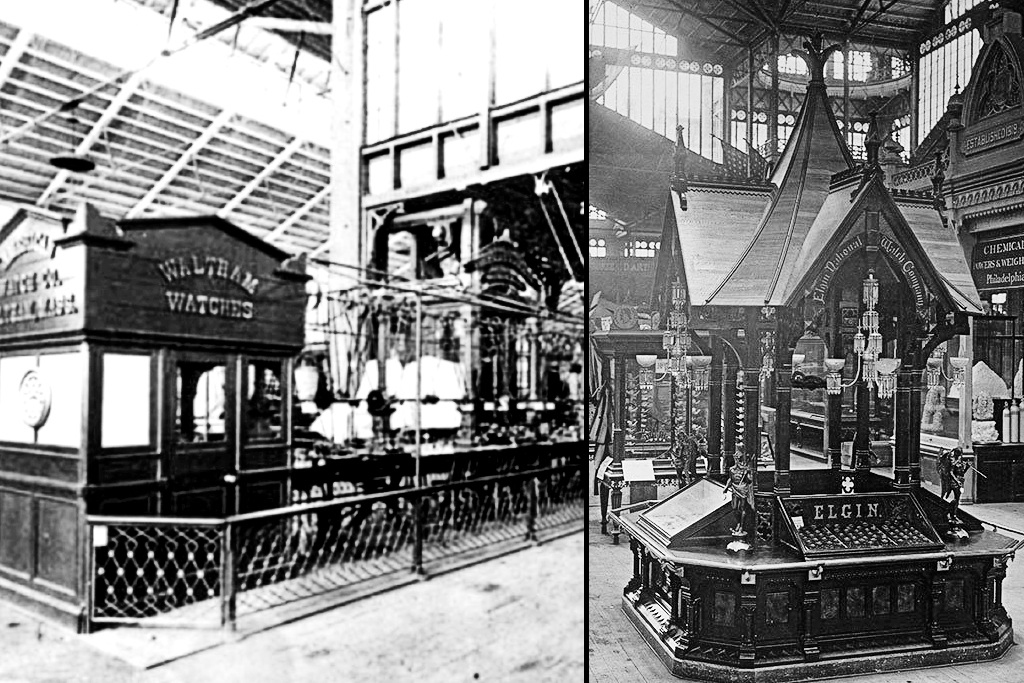

The American watch industry continued to advance enough that by 1876, annual Swiss exports to America had dropped to 4.8 million francs, down massively from 17.1 million five years earlier. Swiss industry rep Edouard Favre-Perret was sobered by what he saw from American manufacturers at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition. He told his peers that “it has been complacently repeated that the Americans do not make the entire watch. This is a mistake. The Waltham Company make the entire watch–from the first screw to the case and dial.”

And so Jacques David was then sent to the United States to study American watchmaking methods on behalf of Swiss watchmakers. Author and watch historian Richard Watkins notes, “Because the American manufacturers cooperated with their Swiss guests, David’s reports on their technology cannot be viewed as industrial espionage.” After all, Americans did still import a good amount of Swiss parts, so it was likely that they simply respected him as a peer.

David returned home and delivered a detailed report warning that Swiss watchmaking would be destroyed unless they adopted American-style mechanization and industrial organization–which they did, while retaining some Swiss sensibilities of course.

Railroad Standards and the Heyday of the American Watch Industry

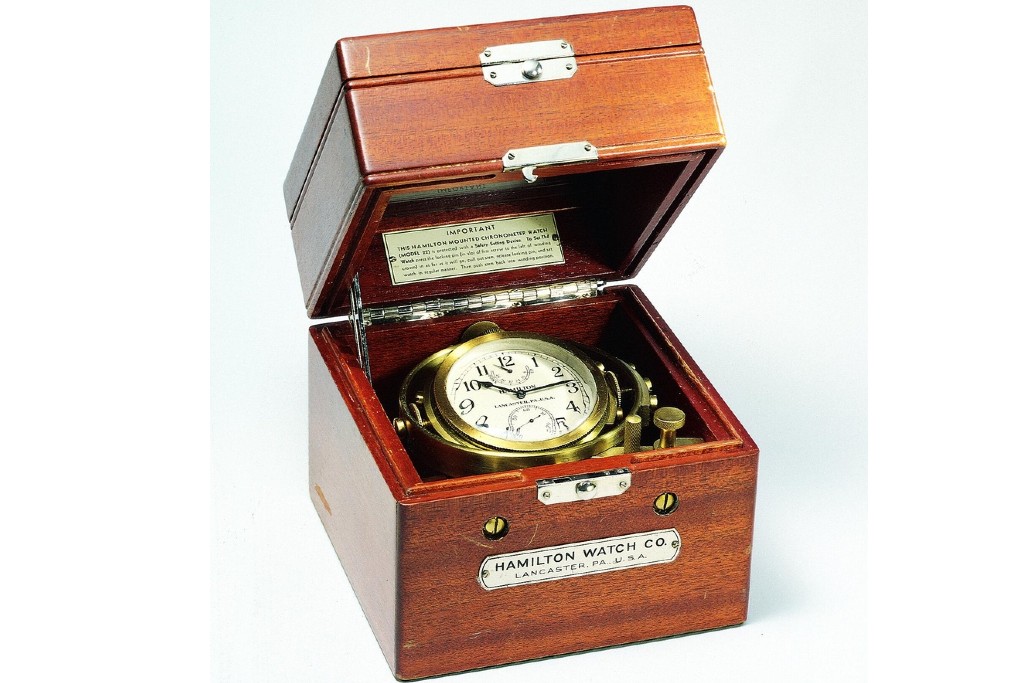

By the 1890’s, the American watch industry was really humming along. You might hear Waltham, Elgin, and Hamilton called the “big three” of early high-quality American watchmaking. Waltham was the original, and Elgin became the volume leader (among high-quality brands). Hamilton was the third-biggest, making revered models like the 992 and 950B.

I also think it’s fair to include Illinois and Ball in a “big five” of noteworthy names in American watchmaking history. Illinois wasn’t making as many watches as Elgin, for instance, but they were known for long power reserves and ornate movements. Their “Bunn Special” is legendary among collectors. Ultimately Illinois was acquired by Hamilton. There were numerous other notable watch manufacturers in the US then, too, like E. Howard & Co., Seth Thomas, Rockford Watch Company, South Bend Watch Company, and Hampden Watch Company.

Ball’s Place in History

Ball, though, didn’t start as a watch manufacturer at all. Webb C. Ball began as a jeweler in Cleveland, Ohio, and his early adoption of standardized time (using time signals from the Naval Observatory) set him apart as a timekeeping expert in the city.

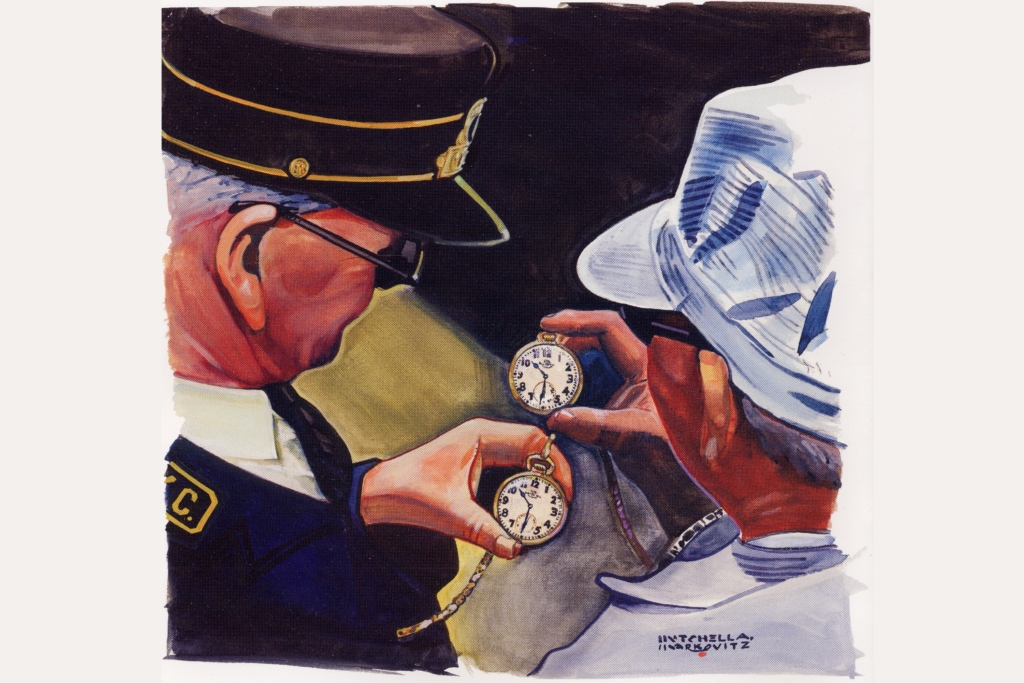

He rose to prominence after a tragic and infamous head-on train collision in Kipton, Ohio in 1891. The accident was caused when an engineer’s watch had stopped for four minutes, leading to a fatal miscalculation and the deaths of several railroad workers. In response, railroad officials appointed Ball as “Chief Time Inspector” and tasked him with creating a system to prevent such disasters from ever happening again.

In addition to a list of manufacturing standards for watches, Ball also wanted inspectors to regularly check their timekeeping. Here are Ball’s standards for railroad-worthy watches in 1893:

General Railroad Timepiece Standards Commission – 1893 Guidelines

| Case | 16 size (~43.2mm) or 18 size (~43.9mm) with no lid, and stem at 12 o’clock |

| Jewels | 17 minimum |

| Setting | Lever mechanism for time-setting (The case had to be opened to set the time, so no accidental adjustments. Note: this has nothing to do with the escapement; “Swiss lever” means something else) |

| Adjustment | Tested in 5 positions at temperatures ranging from 34-100 degrees Fahrenheit, and for isochronism (meaning it can run precisely with the power reserve full or low) |

| Escapement | Double roller escapement, steel escape wheel |

| Dial | White with Arabic numerals |

| Hands | Black, easy to read |

| Accuracy | ≤30 sec/week deviation |

| Inspection | Regular inspections recommended (later codified as twice per month) |

Note that these standards were not always universally enforced. Until about 1908, watches with at least 15 jewels that were tested in at least 3 positions seemed to be tolerated. Plus, standards evolved, and they weren’t always accepted everywhere at once–the Rio Grande Railway began requiring Breguet hairsprings in 1902, for instance. But the table above should give you the general idea. Modern-day watch collectors will likely see similarities between these standards and the Swiss chronometer certification standards that came many years later.

Ball parlayed his notoriety in the timekeeping realm into a watch brand, and he ordered watch movements to his specifications from leading American companies like the ones I’ve mentioned. His company performed the final testing, fine adjustment, and in many cases, casing. They adjusted the watches for accuracy, reliability, and compliance with railroad standards. Once adjusted, the watches were branded and sold as Ball watches, often under the “Official RR Standard” (ORRS) designation.

Fun fact: Omega once made a Railmaster that closely resembled a Ball Trainmaster, and Ball supposedly sued them over the “Official Standard” text on the dial. But that was long after Ball’s heyday. Few of the great names in American pocket watches were very relevant past WWI, but let’s talk about one that was.

The Ingersoll/Waterbury/Timex Story

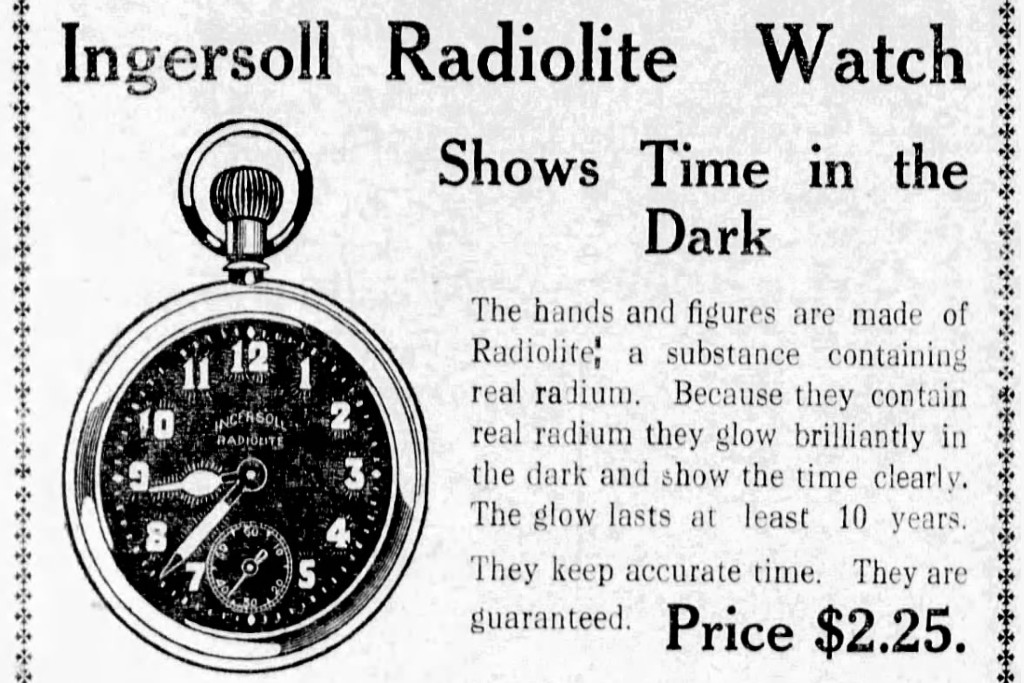

While names like Waltham, Elgin, and Hamilton get plenty of attention from historians and enthusiasts, Ingersoll doesn’t–and they probably sold more watches than all three of them combined. So why does Ingersoll get so little attention despite having sold an estimated 96 million watches in their day?

Well, that’s because collectors focus on high-quality items, and most Ingersoll watches were cheap. Historically cheap, in fact–Ingersoll was proudly the first brand to release a watch for $1. These “dollar watches” generally had unjeweled movements. That’s right, zero jewels–so it’s no wonder that most of them have been lost to the sands of time. But that doesn’t mean they don’t deserve some credit for democratizing watch ownership.

Ingersoll started as a retailer, not a manufacturer–Waterbury Watch Company, founded in Connecticut in 1857, was doing all the actual watchmaking at first. Even as Ingersoll opened their own factories in Connecticut and New Jersey, and acquired Trenton Watch Company and New England Watch Company, Waterbury remained an important supplier of their dollar watches.

Waterbury also played a notable role in early wristwatch history. They were among the first American companies to supply wristwatches to the U.S. military by converting their Ingersoll “Midget” pocket watches into wristwatches with canvas straps and luminous dials during WWI. Waterbury was one of the biggest watch producers in the world at that time.

Ultimately, Ingersoll went bankrupt in 1921 and Waterbury bought them. The Mickey Mouse watch is often credited with keeping the reorganized Ingersoll-Waterbury company alive during the Great Depression, but financial problems persisted. In 1942, Norwegian investors led by Thomas Olsen and Joakim Lehmkuhl purchased the company.

Wartime Pivot

During WWII, Ingersoll-Waterbury became a critical supplier of precision timers for bomb fuses and other defense products, moving away from consumer clocks and watches. In December 1944, shareholders voted to rename the company United States Time Corporation, reflecting its new identity as a major defense contractor. After the war, the company leveraged their manufacturing expertise to re-enter the consumer market, eventually launching the Timex brand in 1950.

US Time would continue to make various non-watch products for many years (in fact they were the original manufacturer of Polaroid cameras), even after they were renamed Timex Corporation in 1969. Since the 1980’s, though, Timex’s focus has squarely been on watches.

Timex’s Early Commercial Success

Timex always focused on affordability, so they intentionally sold their watches at places like drug stores, which had lower markups than fancy jewelry stores. Using bearings made of their proprietary alloy Armalloy (instead of synthetic rubies) also kept the cost down, as did their massive scale.

Durability was also important to Timex. They were an early adopter of television advertising, and their “Takes a licking and keeps on ticking” ad campaign was a massive success in the 1950’s. When Seiko released the world’s first quartz wristwatch for sale in 1969, Timex had captured roughly half of the American wristwatch market.

Timex’s Quartz Transition

Timex seemed to be the only major American watch brand that quickly embraced Asian electronics manufacturing. While Timex used American-made quartz movements early on in the quartz era, they built two factories in the Philippines in the 1970’s and would continue to build more factories in places like India and China. Timex managed to stay relevant with releases like the Ironman in 1986, and their famous Indiglo backlight in 1992.

Other former titans of the American watch world like Hamilton, Bulova, Elgin, and Waltham simply fell by the wayside. Today, Hamilton is a Swatch brand, Bulova is a Citizen brand, Elgin is owned by a Chinese holding company, and Waltham is a Swiss-owned brand that makes Soprod-powered homages of WWI-era Walthams.

Timex’s embracing of Asian manufacturing proved wise, though they were purchased by a Dutch conglomerate in 2008 so they’re not even headquartered in the US anymore, either. Let’s back up and look at the last time the Americans were major players in the watch industry.

The Early Battery-Powered Era

Hamilton unveiled the world’s first electric watch in 1957. There’s a big difference between electric and electronic, though. The Hamilton Electric 500 had no transistors or circuits–it was powered by a battery, but the timekeeping mechanism was still mechanical. Collector and watchmaker accounts suggest that, when new and properly maintained, the 500 could achieve accuracy in the range of ±10 to ±30 seconds per day.

That was better than a typical mechanical watch back then, but not that much better. Plus, Hamilton’s electric movements were notoriously finicky. And something far superior came from another American company just a few years later.

Bulova Accutron: The American Watch Industry’s Great Hope

Bulova had already experienced some success in the post-railroad American watchmaking era, and they even made the world’s first television commercial in 1941. But their most famous contribution came almost two decades later. The Bulova Accutron, released to the public in 1960, is widely hailed as a massive success story of American watchmaking.

In fairness I should note that most of the key development of the Accutron was done by Swiss engineer Max Hetzel while working at Bulova’s Bienne facility. But he later fine-tuned his design while working at Bulova’s New York headquarters. Regardless of how “American” you feel it is, the Accutron was the world’s first electronic wristwatch, and its tuning fork-based movement was much more accurate than mechanical watches of the day.

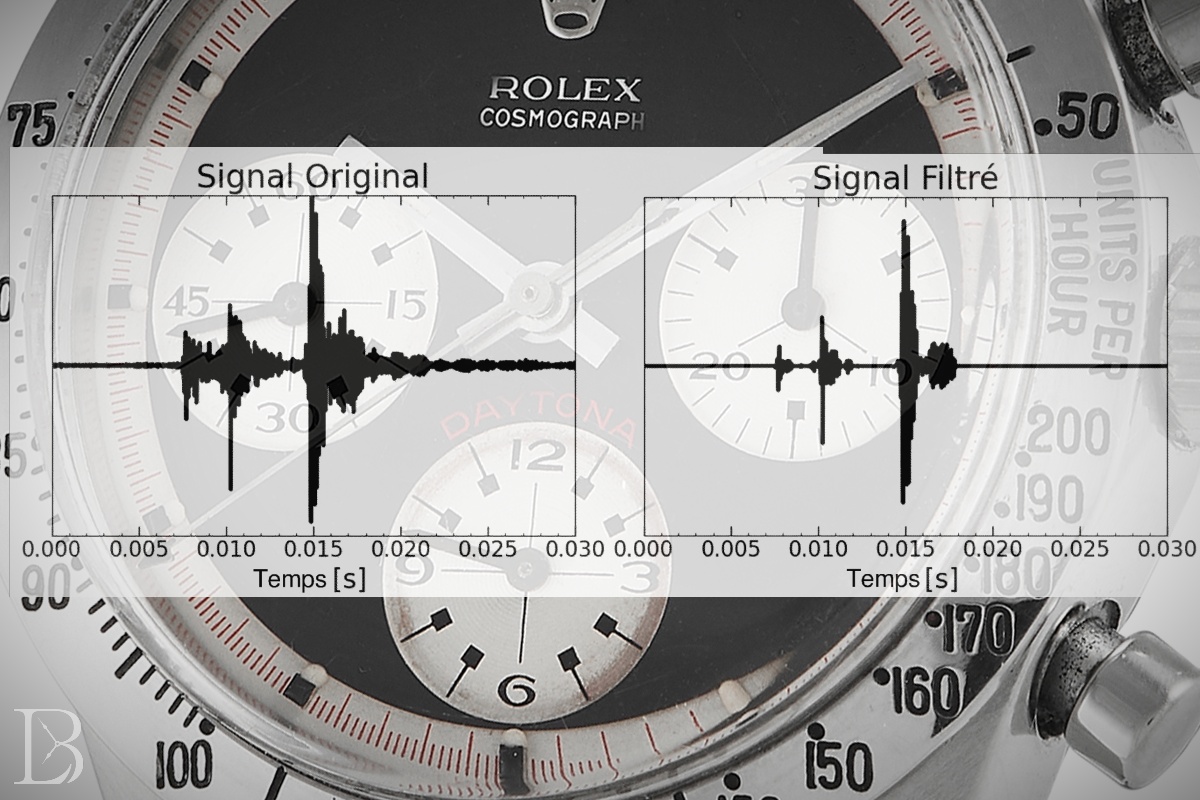

Leading Swiss brands like Rolex were deeply concerned about the Accutron. The book Selling the Crown details how Rolex basically engaged in full-blown corporate espionage to keep tabs on Bulova; that’s how worried they were. The Accutron was only destined for one decade of glory, but in the early 1970’s, when quartz watches were new, the Americans made one final major “first” in watchmaking history.

Hamilton Pulsar: The First Digital Watch

The Hamilton Pulsar P1 debuted in 1972 with a groundbreaking LED display, clearly displaying the time in numerical format. It was the world’s first wristwatch with an electronic digital display. The electronic circuitry was designed and largely assembled by Electro/Data Inc. in Texas, while the integrated circuits themselves were sourced from major American electronics manufacturers like RCA and Hewlett-Packard.

Unfortunately for the Americans, Seiko came out with a far more energy-efficient LCD screen the very next year, and the American watchmaking industry rapidly fell off the face of the Earth.

Geography of American Watchmaking Industry

The US used to have major watchmaking industry in 8 states, and it all crumbled. Here’s a breakdown of the geography of America’s historically significant watch companies:

| State | Major Historical Brands | Notable City/Cities |

|---|---|---|

| Massachusetts | Boston Watch Co./Waltham Watch Co., E. Howard & Co., Hampden (originally Springfield) | Waltham, Roxbury, Springfield |

| Connecticut | Seth Thomas Watch Co., Waterbury Clock Co. (later Timex), Ansonia Clock Co., Benedict & Burnham, Ingraham | Thomaston, Waterbury, Bristol |

| Illinois | Elgin National Watch Co., Illinois Watch Co., Rockford Watch Co., Aurora Watch Co. | Elgin, Springfield, Rockford, Aurora |

| Ohio | Ball Watch Co., Columbus Watch Co., Dueber-Hampden (after move from MA), Gruen (later years) | Cleveland, Columbus, Canton |

| Pennsylvania | Hamilton Watch Co., Keystone Watch Case Co., Adams & Perry, Lancaster Watch Co., Dudley Watch Co. | Lancaster, Philadelphia |

| Indiana | South Bend Watch Co. | South Bend |

| New York | Ansonia Clock Co., Ingersoll Watch Co., New York Standard Watch Co., Gruen (early years) | New York City, Brooklyn |

| New Jersey | Trenton Watch Co. (originally New Haven Watch Co.) | Trenton |

There was also a blip of Californian watchmaking in the late 1800’s, and I should shout out Rhode Island for being the birthplace of the stretchy watch bracelet. Arthur Hadley, a Providence-based jeweler, made an early stretchy bracelet in 1913. And another Providence company, Spiedel, would perfect the concept with the Twist-O-Flex in 1959 (based on the German Fixoflex design).

Twist-O-Flex bracelets were the go-to affordable replacement watch bracelets for decades! Although these “hair-puller” bracelets are now out of style, it’s remarkable what a high percentage of well-worn old watches have ended up on Twist-O-Flexes.

The American Watch Case Industry (NY/PA/NJ)

Before I talk about the tattered remains of the modern-day American watchmaking industry, I should also mention the once-formidable American case-making industry. There is a long history of American companies casing up imported movements–not just from Switzerland, but England as well. This was occurring even in the late 1700’s.

“I believe there were two types of dealers who cased English watches in the US. One group was those who considered themselves watchmakers and put their own names on movements which they had cased. The other was gold- and silversmiths who imported movements with their English makers’ names and made the cases themselves.”

Dr. Jon of the NAWCC forums

There were a huge number of American watch case companies in the 1800’s. The Pocket Watch Database lists more than 400 American watch case companies, with over 40% of them being based in New York state. The greatest achievement of New York case-making was undoubtedly the Depollier case–the world’s first waterproof watch case!–in the WWI era. The Oyster was not the first waterproof watch; that’s a pervasive Rolex myth. Various movements and brandings were applied to Depollier cases, with the “Waltham Field & Marine” being the most well-known version. Depollier probably bet too heavily on military contracts during WWI and failed to maintain commercial relevance once the Oyster was out.

In the 1950’s-1970’s, in part due to high tariffs on complete gold watches at the time, many Rolexes sold in the US used locally made cases. Rolex sourced cases from at least three New York firms (Pioneer, I.D. and Lapwell) for some of their American-market non-Oyster watches, such as the “Long Island Rolex” ref. 7002.

New Jersey and Pennsylvania were also major hubs for case makers. Most of them didn’t survive past WWI, but a reasonably healthy American watch case industry continued to exist until the 1970’s.

The Swift Downfall of the American Watchmaking Industry

Although the term “quartz crisis” continues to get thrown around a lot, the crux of the issue wasn’t quartz watch movements per se. It was never really a “quartz crisis,” but a “how do we compete with Asian manufacturing?” crisis, and it’s hardly unique to the watchmaking world. We should keep in mind that Grand Seiko mechanical watches were already mopping the floor with their Swiss counterparts at the Geneva Observatory competitions in 1968–before they even sold quartz watches.

The Swiss managed to survive Asian competition thanks to a combination of savvy consolidation, some breakthroughs in plastic parts manufacturing that made Swatch watches possible, and good marketing. Nicolas Hayek gets a lot of credit for saving the Swiss watch industry by orchestrating the mergers that created the Swatch Group today, and rightfully so. But it should be noted that the gears of Swiss hyper-consolidation had already been turning for decades at that point, with the state-backed ASUAG dating back to 1931 to help the watch industry survive the Great Depression.

And if you’ll notice, there are a massive number of random Swiss brand names that appear on watch dials from the 1950’s-1970’s that just happen to say “17 Rubis Incabloc” in the same font. I believe most of those were simply brand names owned by A. Schild or a few other giants; Swatch was not exactly the first Swiss mega-conglomerate.

Regardless, Americans never seemed to attempt the same level of consolidation. Although brands like Bulova and Hamilton saw some success well into the 1970’s, the American watch industry never really recovered from the Great Depression. The rise of Asian manufacturing was just the nail in the coffin.

More on the Swatch Group:

| ➢ | Breguet Serial Numbers Explained |

| ➢ | Are Omega Watches a Good Investment? |

| ➢ | The Best Entry-Level Blancpain Watches |

| ➢ | Glashütte Original Seventies Chronograph “Watermelon” and “Swimming Pool” Dials |

The Future is Micro?

The US no longer produces a significant volume of watches, but it’s worth noting that its wristwatch maintenance market is massive. There are still enough watchmakers in the United States to warrant trade organizations like the American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute, and good watchmakers are in such demand that Rolex at one point offered free 18-month watchmaking courses–housing included–at their Dallas facility. And Bulova supports the Veterans Watchmaker Initiative, which offers watchmaker training to disabled veterans at no charge.

The day-to-day work of today’s American watchmaking industry largely revolves around servicing Swiss watches, and there are no signs of a resurgence of large-scale American wristwatch production. But there’s no reason American watchmakers can’t make their own successful, small, artisanal brands.

RGM, Weiss, Avoirdupois Manhattan and J.N. Shapiro, the only current American brands that truly manufacture their own in-house movements, are the most obvious examples. Oregon-based Keaton Myrick notably uses ETA base architecture for his spectacular $30,000+ watches, but he makes about 80% of his movement parts himself.

So, American (or at least 80%+ American) movements do exist, but very few are produced. RGM and Weiss continue to offer more affordable ETA-based but American-finished options, while J.N. Shapiro seems content with its ultra-luxe low-volume status. Avoirdupois is definitely making waves by offering a fully USA-made (down to the hairspring!) watch for under $15,000, so keep an eye on them.

As impressive as that is, I don’t think every American watch brand needs a fully in-house movement; I believe most of today’s watch enthusiasts can appreciate high-quality small-batch finishing even if applied to a mass-produced base part. And luxury watch buyers seem increasingly willing to consider–or even prefer–obscure independent artisans. So although today’s watch landscape has become saturated with what I call “dropdown menu microbrands” that do little more than choose configurations from AliExpress suppliers, I think there is still plenty of room for small watchmaker-centric brands. And there’s no reason the American watchmaking industry can’t be part of that.

Leave a Reply