Rolex Engineers a Self-Correcting Optical Atomic Clock

Rolex sometimes gets accused of “not innovating” because of their relatively conservative watch design evolution, and because they don’t offer exotic complications like perpetual calendars, tourbillons or minute repeaters. But in reality, Rolex employs multiple teams of world-class scientists–such as the ones at Rolex Quantum SA in Neuchâtel–who quietly make technical breakthroughs on a regular basis. Recently, Rolex applied for a patent for a new type of optical atomic clock that uses an error-reducing “mitigation laser” in addition to its main one. Let’s get into it.

What is an Atomic Clock?

Before we go any further, I should define what an atomic clock is: any clock that uses a specific atomic transition (namely, atoms going back and forth between two well-defined quantum energy levels) as a timekeeping reference. Basically, certain atoms have a built‑in resonance frequency (“sweet spot” if you will) at which their internal energy jumps between two specific levels at a very predictable rate. This rate is used to continuously super-fine-tune a quartz oscillator, not replace it entirely.

For example, when you excite Cesium-133 with a microwave field oscillating at 9,192,631,770 Hz, the atoms switch back and forth predictably between two distinct low-energy states. If the energy “jumps” slow down, that means the oscillator has drifted from 9,192,631,770 Hz and it immediately adjusts accordingly. Electronics can readily count oscillations in electromagnetic fields, so if you count 9,192,631,770 oscillations, assuming the oscillator has been continually tuning itself to the atoms as it should, that’s one second.

In fact, while seconds used to be officially based on solar time (the earth’s actual rotation), because the earth’s rotation is slightly irregular, the scientific world now defines a second as 9,192,631,770 cesium cycles.

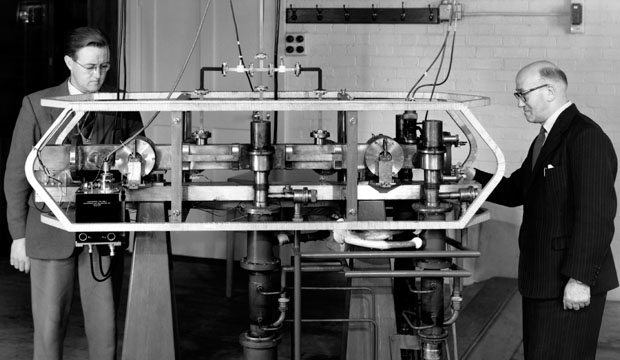

The Maser ammonia clock was technically the world’s first atomic clock in 1949, but Cesium-133-based atomic clocks are orders of magnitude more accurate. It would take tens of millions of years for a cesium beam clock to be off by one second, and hundreds of millions of years for a cesium fountain. A cesium beam clock shoots fast, hot atoms past the microwave field for only a few milliseconds, while a cesium fountain clock first laser-cools the atoms and tosses them up so they drift slowly through the microwaves for about a second, giving a much cleaner measurement.

Cesium fountain clocks based in laboratories have been the “gold standard” of timekeeping for decades, but cesium beam clocks are more likely to be found in everyday commercial use, for instance onboard large ships. Hewlett-Packard was a major producer of cesium beam clocks before they spun off that business.

Non-Cesium Atomic Clocks

Rubidium clocks use the same principle as the Cesium-133 ones–use an oscillating electromagnetic field tuned to the “hyperfine transition” (the gap in energy between two states) of a certain atom and count the cycles. They have been workhorses in the telecom industry for years. Hydrogen maser clocks are slightly different, and use the hyperfine transition of hydrogen. They’re extremely quiet, so they’re popular in fields like radio astronomy where silence is important.

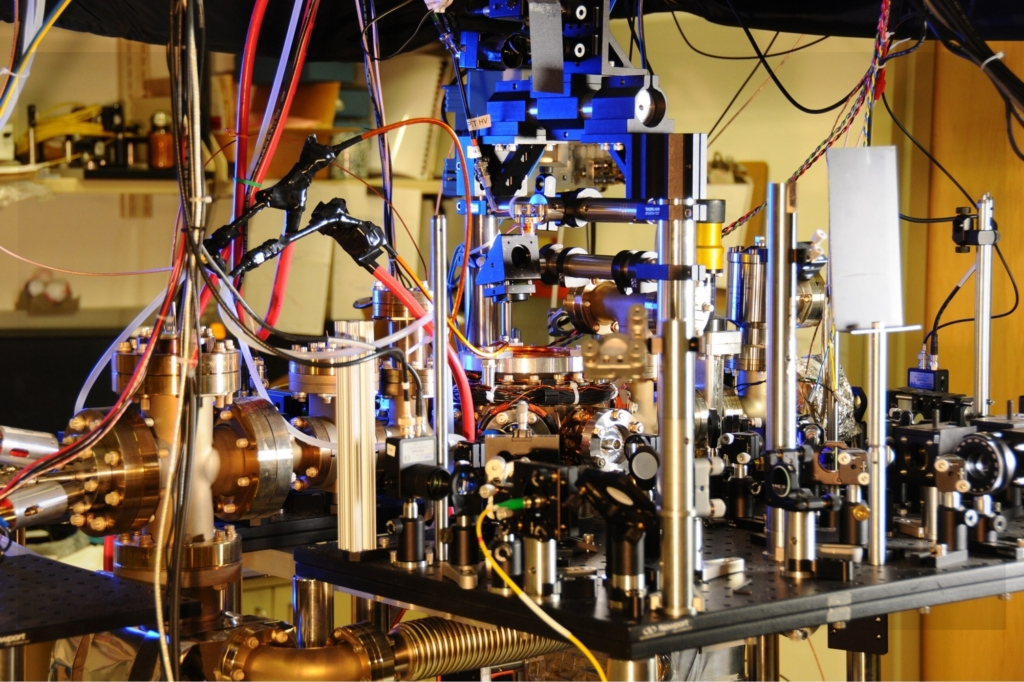

But the newest type to emerge is the optical atomic clock, which uses lasers instead of microwaves. At the right frequency, light can cause certain atoms to fluoresce (glow), and theoretically, you can count those flashes of light to keep time. This concept was explored in the early 1970s, and the first example of an optical clock appeared in 2003, in part made possible by the invention of optical frequency combs. While computers are perfectly capable of counting millions of cycles per second, for lasers you’re talking about hundreds of trillions of cycles per second–way too fast even for a modern computer.

Think of two linked “gears of light”: a tiny fast one and a big slow one. The optical frequency comb lets you phase‑lock those gears so every turn of the fast gear corresponds to a well‑defined tiny turn of the slow gear, and then you only have to watch the slow gear. This “gears down” the oscillations to a countable range. The most accurate clocks in the world are currently optical lattice clocks, which are roughly 100x more accurate than Cesium-133-based ones, and they could very well redefine the definition of the word “second” someday. But they are large and only suited for laboratories.

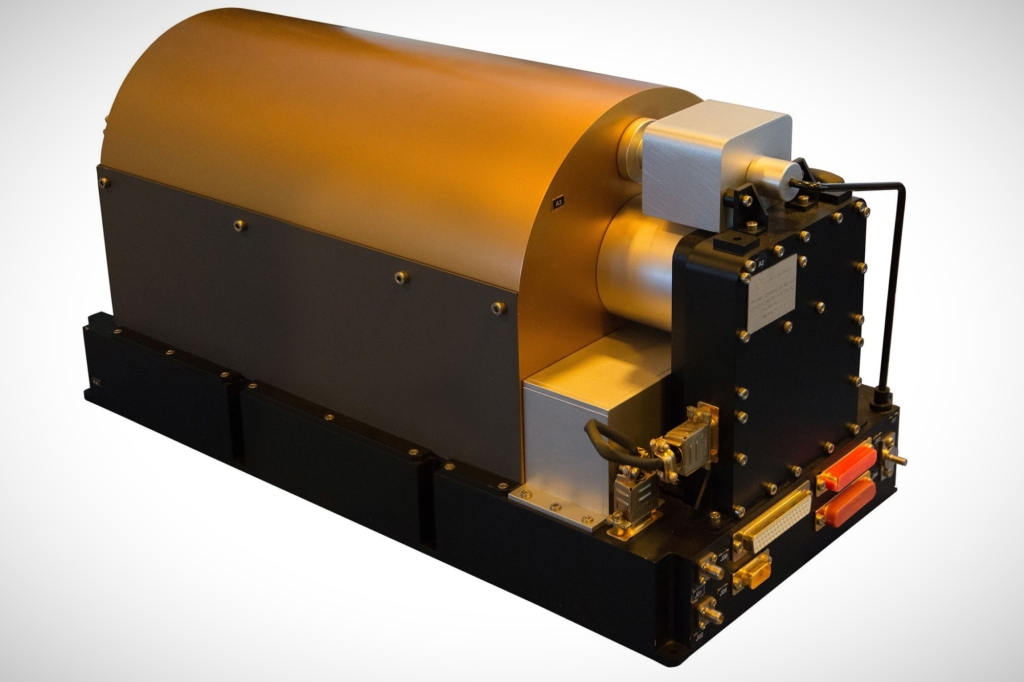

Kyle Martin et al described a smaller optical atomic clock in 2019. It’s a “two‑photon” clock, meaning the atom absorbs two photons at once whose combined energy matches the energy gap of the transition. Although it isn’t quite as absurdly accurate as the optical lattice types, there is a constant need for accurate but compact reference clocks in devices like satellites and networking equipment. Rolex’s patent seems to be for a Martin-style optical atomic clock, but that design had one weakness: AC Stark, or “light shift.” That means that the light photons that you’re shooting at the atoms to measure them, also push and pull on the energy levels themselves, shifting the very transition frequency you are trying to lock to. So there was some timekeeping “drift” over time. But Rolex engineered a solution for that.

What is Rolex’s Atomic Clock Patent Application For Exactly?

Rolex’s patent application WO2025233363A1 describes a compact two‑photon rubidium vapor optical clock with a crucial novel feature: a “mitigation laser” designed to counteract the light shift caused by the main “interrogation” laser. This second laser operates at a different wavelength (the patent gives 785 nm or 1556.2 nm as examples) that produces a light shift of opposite sign to the shift from the 778.1 nm interrogation light, so with the right power ratio the net shift of the clock transition can be nearly cancelled.

The total light power is deliberately modulated at a test frequency; if there is residual light shift the atomic signal “wiggles” and a servo (feedback controller) adjusts the mitigation laser power until that wiggle disappears. These optical clocks should be compact enough not only to be used at Rolex’s growing number of service centers as reference clocks, but also to be sold to the telecom and aerospace industries. For a brand that has only made timepieces for well over a century, a foray into leading-edge electronics would certainly be notable. But as always with Rolex, time will tell what (if anything) they do with this patent-pending technology.

Who Invented This?

Rolex‘s invention builds upon decades of work by various brilliant scientists, but Fabien Droz is listed as the primary inventor, which makes sense because, as reported by Arcinfo, he’s the director of Rolex Quantum SA. The other inventors are associated with CSEM (Centre Suisse d’Électronique et de Microtechnique) which is a non‑profit, public‑private R&D center that Rolex collaborates with. In the spring of 2025, Rolex Quantum opened near CSEM, located (appropriately enough) right next to the Neuchâtel Observatory, where the standard reference time was once measured by looking into space.

This patent application looks like it could be the first big win for Rolex Quantum. So the next time someone tells you that Rolex isn’t innovative, you can ask them which watch brand has a quantum physics laboratory that they prefer. This new Rolex atomic clock could very well become an industry standard in avionics someday.

Leave a Reply